Learning to Learn

Learning benefits from deeper curiosity, memory, and connection. Build a system to improve all three.

“One day about three or four years after I joined, I discovered that John Tukey was slightly younger than I was. John was a genius and I clearly was not. Well I went storming into Bode's office and said, how can anybody my age know as much as John Tukey does?”

He leaned back in his chair, put his hands behind his head, grinned slightly, and said, “You would be surprised Hamming, how much you would know if you worked as hard as he did that many years.” I simply slunk out of the office!”

—You and Your Research, Richard Hamming

Knowledge compounds. Let’s explore how to do so more effectively.

Education is flawed in many ways but it’s criminal that we aren’t explicitly taught about:

Memory: how to remember what we learn

Nurturing ideas: how to clarify and build our thinking over time

Curiosity: how to fuel our learning engine

The school system certainly treats our memory and insights as skills to be improved, but one generally gets the feeling that we either have them or we don’t. That now strikes me as far from the case. Below are the habits and tools that I found to be useful when it comes to remembering and connecting what we learn. This essay isn’t meant to be comprehensive, but it is meant to highlight the approach that currently makes the most sense to me.

What I’ve learned has completely changed the way that I read and reflect. I hope you find it as useful as I do.

Let’s start with point 1: memory

Learning can feel like wading through a dense fog. Fact by fact, our forward vision crystallizes, but day by day, often hour by hour, the fog that we fought so hard to clear resettles behind us. We’re often lucky if, after a week, we have a few clear lines of sight to what we originally learned.

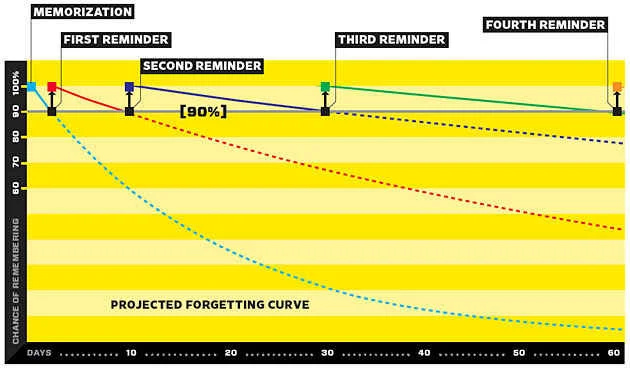

To our best current understanding, this fog rolls in on an exponential schedule. It’s called the Forgetting Curve, and it looks something like this (where the dotted lines highlight our chance of remembering without review):

Notice that as time goes on without review, your chance of remembering dips markedly. However, with periodic review, there’s a much happier ending in sight. Let’s worry about that shortly.

First, let’s consider: Why is it easier to remember some things than others?

Let’s take language as an example. If I give you two Chinese characters, 中文, how likely are you to remember them in a week?

Barring a background in Mandarin, not very. But what if I told you that they mean “Chinese language” and mentioned that the first looked like a flag (“Chinese”) and the second as an acorn with two legs (not quite "language,” but it should do). That gives you a fighting chance.

There’s a strong connection between what you know and what you can learn. The more knowledge that you can weave into something, the more likely you are to remember it. Applying this to a different example, how do concert pianists remember thousands of pages of sheet music? The preceding 999 sheets support the 1,000th, and so on.

That works well, but it takes time and effort to build up the background needed to make connections in the first place. What about information that just won’t quite stick?

Here’s where we come back to the Forgetting Curve. Notice that each time material is reviewed, the memory curve flattens out. That highlights how reviewing at the proper moments makes you that much more likely to remember. This is particularly useful for information that isn’t connected to other information yet.

How do you do that in practice?

One option is Anki. Anki is spaced repetition software (SRS) that lets you turn your learning into digital flashcards. The software then prompts you on an exponential schedule based on these questions. This does something that quickly becomes impossible with large amounts of physical flashcards—it quizzes you at the right moment (or at least as close as an exponential scheduler can get). This software currently requires you to input the questions yourself, which can be time-consuming. But in my experience, it’s more than worth the time it takes to do so.

Quizlet and Duolingo both play off of similar spaced repetition. I’ll come back to this when explaining what my process looks like.

Takeaways:

Connection complements memory. For material with too little connection or material that you’d like to revisit, spaced repetition software is invaluable.

And now point 2: processing

== WIP (I wanted to get this out there; hopefully it’s useful! I’ll be continuing to write over time) ==

Takeaways: Think through and connect what you learn away from the source material (make sure that it is firmly understood and in-memory).

Finally, Point 3: curiosity

What is curiosity? Curiosity, put simply, is motivation to learn. For me, it feels akin to salivating over delicious food. The better prepared the food (or question) is, the more motivation I have.

But we’ve gotten ahead of ourselves. Let’s stay on the topic of what curiosity is. Knowing that curiosity is motivational (some say like rocket fuel), how can we become curious about the things we’d like to know? What helps questions arise in the first place? What makes us want to find the answer? What makes the process meaningful? Let's reverse engineer it.

Curiosity benefits from connection

A single puzzle piece is trivia. A piece that fits into a bigger picture becomes valuable.

Curiosity benefits from headspace & persistence

Our culture is hell-bent on consumption—retail, technology, travel, and most important to this essay: media. With so much consumption and so little space for questions, it's a miracle that we think at all these days.

How do we stay curious?

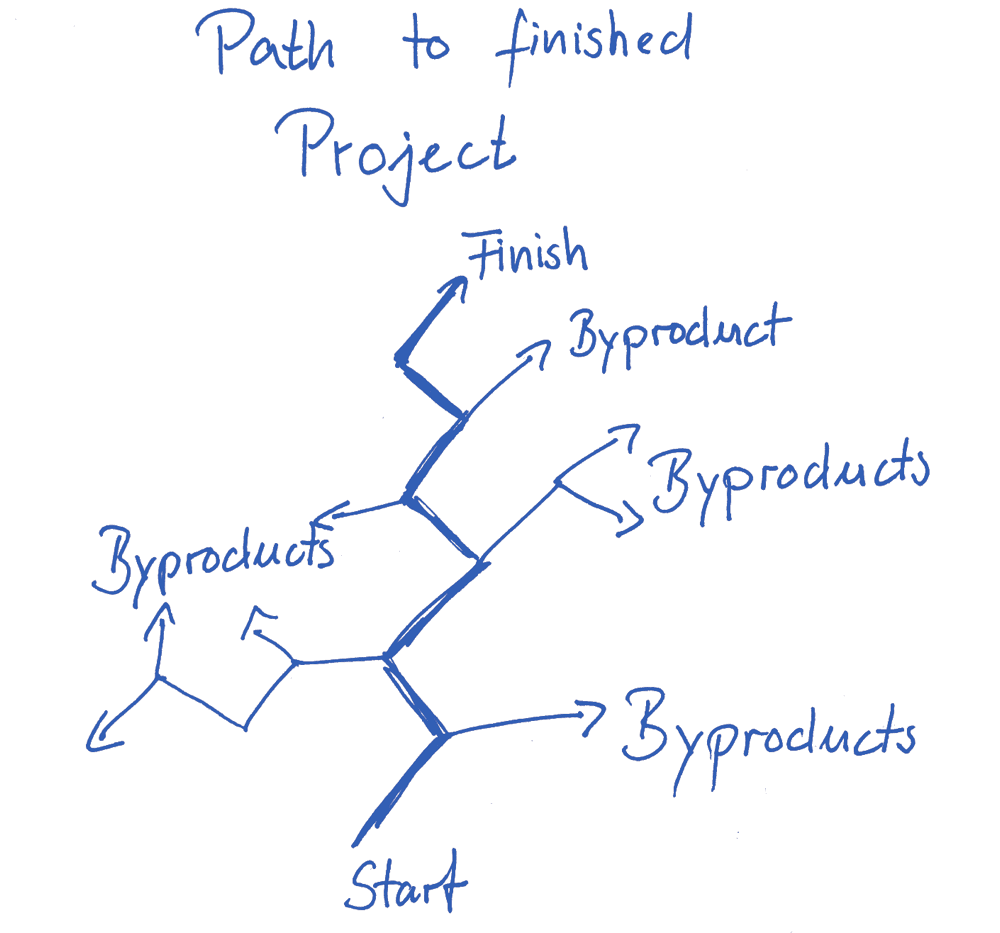

Once we're curious, most of us, far from thinking in a tree-like fashion, find ourselves interested in a subject without identifying the exact questions that we want to answer. Instead, it can be incredibly powerful to identify the specific questions you have in mind. Keeping a scratch pad of those questions, similar to the drawing below, can help keep you focused and motivated.

==WIP==

Takeaways: Curiosity is a give-and-take. Feed it with new information and encourage it by asking questions and leaving space.

So what does my learning process look like?

This is mostly targeted at learning by reading. These same concepts can be applied to audio, visual, or interactive learning as well.

Start the day by thinking. On an ideal day, I spend 30+ minutes writing about what I learned the day before. This not only keeps me accountable to learn something every day, but it also helps make sure that I’m actually remembering what it is that I learned. As an added benefit, new questions often arise that I will then take time to learn about.

This is a shift from note-taking to note-making. Spend time off-line, writing evergreen-style notes with original thoughts. The goal at this point is to shift from consuming information to creating knowledge.

I use the Zettelkasten method. At the highest level, it focuses on the connection of notes and not the collection. Some people refer to it as a second brain. It's generally a simple way to organize your thinking and produce original insights.

More specifically, Evergreen notes should be atomic. For my CS people, they're the equivalent of a single function. The goal is to link between notes, trace knowledge, and build new ideas. This is analogous to combining functions to create a program.

These notes can then be edited, reviewed, reorganized, and explored. All in the name of furthering your understanding. The key principle here is that the more you grapple, the more likely you are to remember and make connections. I've found writing to be the perfect format to do so.

Work with the information while initially reading. Highlight memorable ideas on Kindle, Reader, or in a book.

After finishing a chapter, section, or few pages, try to recall what the most important points are that you just consumed. Imagine explaining it to someone. Then go back and fill in whatever details you were missing.

Writing raw notes is also a good way to do this. It takes a few seconds to think through and put something into your own words.

This step helps you to initially process everything and, if you take notes, to have something to look back on when reviewing in the future.

Try your best to avoid the Collector's Fallacy. Remember that it's about initial processing and potential review.

Create spaced repetition prompts (I use Anki) of important points while consuming and looking back over notes or original texts.

Think about this as a leveled-up version of note-taking. Spaced repetition is often just seen as a way to remember obscure details. But it's incredibly powerful if used correctly. See Michael Nielsen's demonstration of this note-taking style.

Unlike notes, the prompts will continue to come back right before you would normally forget them. This is the most effective learning schedule currently known.

These prompts can be used to remember quotes, concepts, facts, tasks, and questions. They can also bring tasks you'd like to revisit or do back to your attention. Get as creative as possible. The only limits are how you can think to use it.

The benefit is absolutely tremendous. I'm finally remembering the things that I read, and because of the spacing, I'm making connections amongst books and essays that would have been impossible in the past.

Allow ideas to marinate. Review Anki prompts and Readwise daily, and think about the concepts. Note where you don't understand something and where you'd like to know more.

I haven't talked about Readwise much yet, but it's a Kindle add-on that sends 5–15 of your past highlights to your inbox each day. It can also be used for any online web page.

This is the most underrated aspect of spaced repetition. We are what we think about. This daily review becomes the ideal way to consistently bring attention back to the things we want to think about.

Want to learn about physics? Entrepreneurship? Music theory? Japanese? Nolan Ryan's pitching philosophy? Start with basic information, and day by day, continue to build your knowledge on top of it. The brilliant thing is that, when used correctly, spaced repetition will enable you to actually remember things from top to bottom.

Finally, intertwined with these steps: Go on walks. Think concepts through without the source material. Ask questions, answer them. Talk to others. Podcast. Tweet. Grapple with hard problems. Use your new knowledge. Make connections to other disciplines. Create personal projects. Keep asking why.

And finally, remember Gauss, "Praxis tentatum docebit"—practice teaches those who try.

Wrapping up

With all that said, let's come back to the two original examples of what school could have equipped us with:

To remember things, take notes and initially process the material. To do so indefinitely, write spaced repetition prompts to revisit the ideas and avoid the dreaded forgetting curve. Then grapple with the information to create new knowledge. These ideas don't have to be fully original, but they shouldn't be something that you've read before. They should be new to you1.

Learning something fully on your own is a bigger question. Using these tools is a strong step in that direction, along with personal projects and, more generally, using what you ingest. Much of learning is trial-and-error. Don't give up. It will be difficult, but would it be worth it if it wasn't?

Like any system, I built this over time. Try to add one step at a time and see how it goes. If you're unsure of where to start, choose spaced repetition. It's been the most impactful change for me, and something that is criminally overlooked.

Notes

I've often found myself passively going through these steps, especially when tired. I don't think it's bad to work when we're not fully there2, although it can be useful to take breaks or choose to work on other things.

Last but not least, let me know if any of this resonates with you or if you think that any of these steps can be improved. Feel free to comment below or find more contact information on my personal website !

References

My tools: Anki, Kindle, Reader, Obsidian, a good ol’ fashion pencil and notebook

Start here: Augmenting Longterm Memory by Michael Nielsen

“My reading habit has evolved significantly over the past couple of years and surely will continue to. In this post, I will describe how I approach my reading. You may think it’s elaborate (other people’s reading systems rub me the same way); however, keep in mind it’s evolved slowly over the years.”

How to write good prompts by Andy Matuschak

“So we must learn two skills to write effective retrieval practice prompts: how to characterize exactly what knowledge we’ll reinforce and how to ask questions that reinforce that knowledge.”

Evergreen notes by Andy Matuschak

“Evergreen notes are written and organized to evolve, contribute, and accumulate over time, across projects.”

Introduction to the Zettelkasten Method

“The Zettelkasten Method allows you to concentrate on a small part of the problem, and after that, take a step back and look at it with a panoramic vision.”

It's hard to hear yourself think by Andy Matuschak

“I find for myself that my first thought is never my best thought. My first thought is always someone else’s; it’s always what I’ve already heard about the subject, always the conventional wisdom.”

How to Read a Book by Mortimer Adler and Charles Van Doren

"Thinking is only one part of the activity of learning. One must also use one’s senses and imagination. One must observe, remember, and construct imaginatively what cannot be observed."

Spaced Repetition for Efficient Learning by Gwern

“The spacing effect essentially says that if you have a question (“What is the fifth letter in this random sequence you learned?”) and you can only study it, say, 5 times, then your memory of the answer (‘e’) will be strongest if you spread your 5 tries out over a long period of time—days, weeks, and months. One of the worst things you can do is blow your 5 attempts within a day or two.”

About My Book Notes by Derek Sivers

“When I’m reading and come across a surprising or inspiring idea, I save it.

That’s all my notes are. I’m not summarizing the book. I’m just saving ideas for myself for later reflection.”

This is called the generation effect. You are much more likely to remember knowledge or thoughts that you create yourself, as opposed to simply being read.

I find it a useful time for first-reads and scaffold-building.